The greenlight triennial, 2024-09-12 — 2024-10-20

TWO CITIES │ FOUR INSTITUTIONS

SKIEN : TELEMARK KUNSTSENTER │ SPRITEN KUNSTHALL │ SKIEN KUNSTFORENING

PORSGRUNN: KUNSTHALL GRENLAND

ARTISTS: dAMIEN AJAVON │ LARA ALMARCEGUI │ sammy baloji │bigert & bergström│ CHIARA BUGATTI │ TANYA BUSSE │ AYŞE ERKMEN │ cOLLECTIF GRAPAIN │ STINE MARIE JACOBSEN │ KATARINA LÖFSTRÖM │ rINA EIDE LØVAASEN │ SIMON MULLAN │ NEW MINERAL COLLECTIVE │SELMA SELMAN

CURATOR: POWER EKROTH

Since its inception in 2017, the Greenlight Triennial has focused on exploring regional issues concerning nature, industry, climate, and their impact on Grenland‘s scenic landscape. The transformations witnessed in Porsgrunn and Skien, the main nodes of the region, mirror the global shifts in the economies and industries. Over time, Grenland has transitioned from a predominance of oil based traditional heavy industry, to providing large-scale depots for computer servers, and now the area is explored for the potential of mining for minerals and chemical elements required to sustain our modern reliance on electronical tools. The region‘s rich mineral history spans several centuries. Søve gruver, situated east of Ulefoss, was once a site for niobium extraction, which also contained uranium and thorium. During World War II, Germany, as the occupying power, expropriated farms to open a niobium quarry for rocket refinement. After the war, the USA utilized the mines for bomber aircraft and rocket development until they were deemed unprofitable in 1961, leading to Norway ceasing operations. In 2004, it was discovered that the mine‘s waste contained highly concentrated uranium and thorium, posing environmental risks that persist today as the so called Søve-slag has still not been taken care of.

The recent discovery of Rare Earth Elements (REEs) in the region, crucial for electric cars, wind turbines, and smartphones, has attracted global mining interest. The European Union, concerned about China‘s dominance holding around 90% of mining rights worldwide, is particularly invested in reducing dependency. The prospect of large-scale REE extraction in Grenland presents employment opportunities and the potential for substantial tax revenue for the municipality. However, as with any mining venture, there are inherent challenges. Mining can trigger ecological disruption, soil and water contamination, air pollution, and biodiversity loss. Additionally, it produces toxic waste that may cause birth defects and cancer for individuals living near thorium deposits or radioactive waste disposal sites. The toxic waste also needs to be safely deposited for thousands of years, underscoring the complex trade-offs that demand careful consideration.

Against the backdrop of Grenland‘s industrial landscape and its global challenges, the fourth Greenlight Triennial invites international artists with varied perspectives. Some focus on site-specific work, engaging residents in projects or workshops, while others dig deep into mining practices, legal frameworks, and theoretical aspects. The practices of the invited artists interweave themes of climate, economy, material exploitation, and expropriation, inviting spectators to reflect on what justice in a global perspective might mean today. The exhibition will not in any way try to paint a full portrait of the perplexing questions that arise where consumerism and climate issues intersect; instead, it will open some related themes that the invited artists are interested in and allow for various interpretations for the viewers and hopefully ignite even more questions.

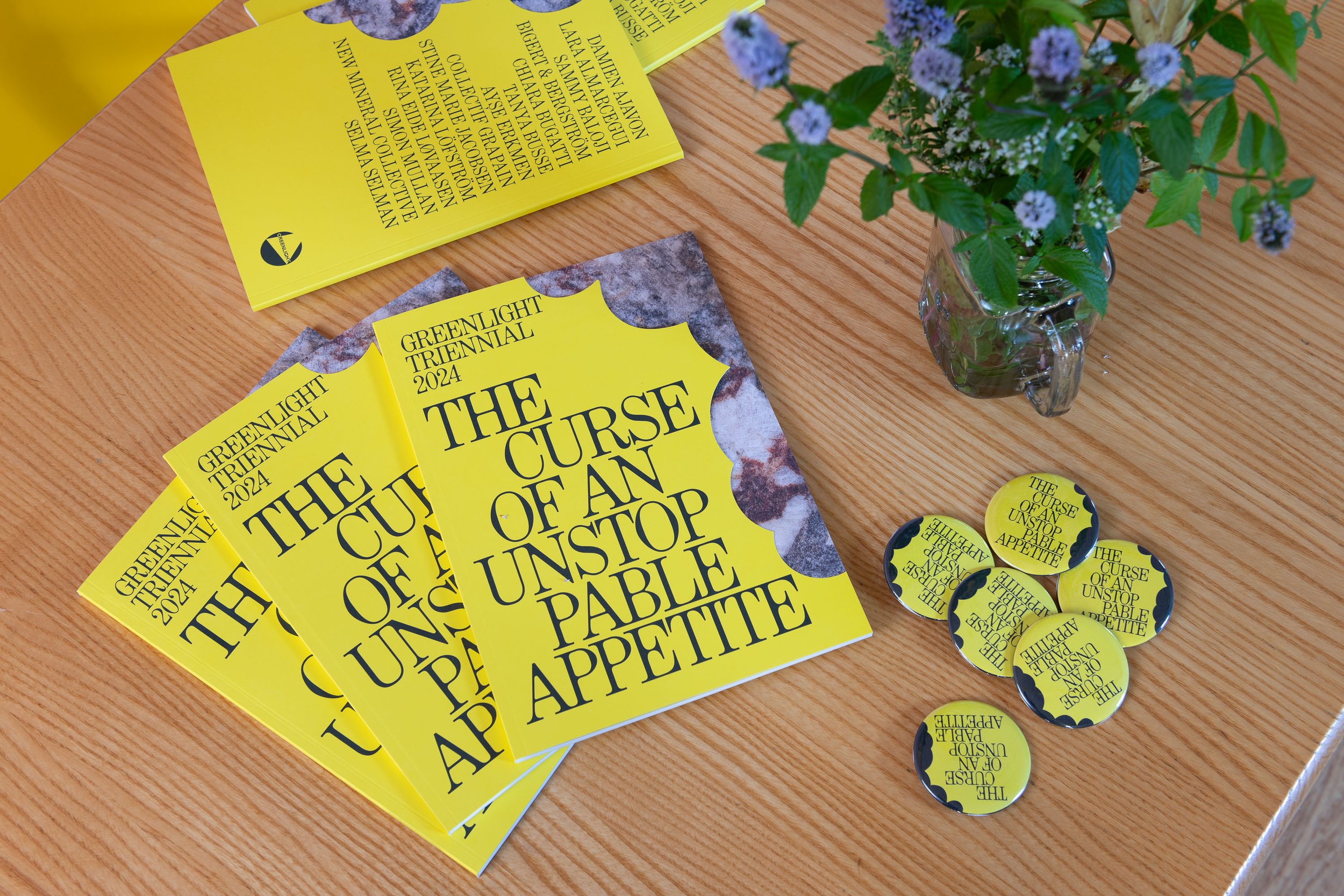

The title for the triennial The Curse of an Unstoppable Appetite draws inspiration from the Greek myth about the Goddess of agriculture and harvest, Demeter, and the (human) king of Thessaly, Erysichton. Demeter cursed Erysichton to live with an insatiable hunger as a consequence of felling a sacred oak. The more he ate, the hungrier he got. As he used all his resources to find food, including his own daughter whom he sold for slavery, he became destitute and desperate. In the very end, Erysichton had to eat himself bite by bite until nothing remained. His desire for food serves as a poignant metaphor for the unrelenting human appetite for more, and the far-reaching consequences it bears.

(scroll down for images from the installations)

Images of the four very different institutions: an old bank - Telemark Kunstsenter; an old rough distillery - Spriten Kunsthall; a newly built center of culture with a white cube setting - Kunsthall Grenland; and a modernist building reminiscing of the atrium at the Neue Nationalgalerie - Skien Kunstforening / Ibsenhuset. Documentation of the catalogue (given away for free) and the various settings for the graphic profile to be seen, and one image from one of the four opening speeches and inaugurations.

EXTRACTION, EXPROPRIATION AND EXPLOITATION

Every day, regardless of whether we live in a cardboard box or a mansion, we engage in basic activities like eating, drinking, sleeping, and of course, pooping. Each seemingly insignificant choice we make – whether it‘s opting for a banana from Honduras for breakfast, indulging in a slightly longer shower, or sending an email – has small yet significant implications. While these choices may appear inconsequential, collectively they could have a substantial impact if everyone followed suit. Furthermore, all our decisions, whether minor or major, reflect moral judgments. Undoubtedly, there is much more we could do on an individual level to mitigate the accelerating pace toward the impending climate collapse warned about by scientists.

Nearly ten years ago, in 2015, Geological Survey of Norway (Norges Geologiske Undersøkelse) NGU and the Norwegian Directorate of Mining (Direktoratet for mineralforvaltning) DMF, estimated that each Norwegian individual consume the mindboggling 13 tons of minerals over only one year. At such a rate of consumption, it seems each member of humanity is cursed by the same spell as Erysichton. However, reports indicate that since 1988, approximately 70 percent of greenhouse gas emissions have been attributed to just one hundred corporations, despite some of them claiming to hold eco-friendly worldviews.

While some of this can be attributed to ignorance, such as failing to recognize the consequences of activities like deforestation, much of it stems from a systemic belief that the Earth‘s resources are commodities to be owned and extracted without regard for consequences or those afflicted. It is notable how the Earth‘s resources, like water or air, are consistently treated as private property, subject to permanent exhaustion as long as they generate profit for the owners, without consideration for future generations. Shouldn’t something that harms the common good be banned?

In the eighties, many of us were distraught by the documentary photography by Sebasião Salgado from gold mines in Brazil. A quick image-search on the Internet for “mining in Congo” with focus on today’s mines cobalt – one of the key components in our mobile phones – is exploited, it is evident that history is repeated. Child labor, abject poverty, workers buried alive, modern-day slavery and sexual assault are the results in these mines. An article from the Inde[1]pendent in 2023 calls it “a nightmarish world in which billions of people are unwittingly complicit”. As long as there is a product with profit to be made, history shows that exploitation follows unless there is a proper legislation that prohibits it by safeguarding individuals and workers’ perspective. When shopping for a new phone, which consumer will actually connect the dots about its relation to slavery, poverty, and assault? In fact, life in our part of the world rather demands that we utilize gadgets that take a heavy human toll.

While these conditions perhaps might seem very far from Norway, the forced assimilation, displacements, and land dispossession resulting in loss of ancestral territories, attempts of suppression of language, culture and traditions – the regular colonial behavior – is something the indigenous Sami people are still facing and fighting close at hand. A recent example in the region is of course the Storheia and Roan wind farms in Fosen in central Norway that, according to Norway‘s supreme court, violated Sami rights under international conventions. Of the many conflicts, the one regarding sea deposition in Repparfjorden for mining waste from the copper mine in Nussir Mountain in Finnmark can also be mentioned. It brings together Sami interests and the environmental movement for actions and protests. Or when Sweden’s government awarded a mining license for an ore in Gállok to the company Beowulf in 2022, after years of protests from the Sami people and environmental activists, scientific experts, and leading international organizations. The company behind the initiative prides itself on making “green energy available safely and affordably in the EU”, while scientists agree that there will be disastrous impacts in the region, and there is stern critique from the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR). And recently, Norway became the first nation to open its continental shelf to commercial deep-sea mineral exploration for an area roughly the size of Italy (280.000 sqm). This, in spite of the opponents that claim that it will irreversibly damage biodiversity and ecosystems, damage the seabed and more damage we cannot possibly foresee.

With existing legislation that prohibits child labor and other safeguarding laws, the mines in the Northern hemisphere will offer a better working environment and better salaries than their counterparts in other parts of the world. The structure of extracting, exploiting and expropriating resources for consumption and profit however remains the same, and the fact that our appetite for the REE is so enormous, means that we undoubtedly always will be dependent on gross exploitation on other parts of the world. The so-called “social license” to operate, which “good working conditions” provide, often becomes a so-called greenwashing argument that creates a myth that we want “Nordic” minerals in our phones or cars, even though it will always be an unlikely scenario since the devices are not produced in the Nordic countries, and these countries do not participate in the market cycle.

THE CAPITALOCENE

The term „anthropocene“ has been widely used since the early 2000s to signify the current geological epoch, characterized by significant human impact on the Earth‘s geology and ecosystems. The human activities, such as industrialization, urbanization, and agricultural practices, have become the dominant force shaping the Earth‘s environment, surpassing natural geological processes. However, it can be argued that only specific activities have been driving environmental degradation and social inequality, rather than human activities in general. Humans have inhabited the earth in harmony for a long time, it is only in the recent few hundred years that the resources have been depleted and the climate entered a catastrophic phase. Recently, an alternative to the term “anthropocene” as the era that has caused most harm to the climate have gained traction, and that is the “capitalocene” – damages done by structural capitalistic actions.

Most of the environmental challenges we face today, such as overconsumption, resource extraction, and pollution, can be traced back to the systemic economic structures and power dynamics that prioritize the maximal accumulation of economic value, making the term “capitoloscene” pertinent. The capitalist economy depends on nature but (unfortunately) not on ecological reproduction, as the latter comes with costs that reduce profit. It is evident that capitalism prioritizes short-term profitability, reminiscent of the idiom “to foul in one’s own nest,” disregarding the accumulating long-term costs. This leads to what the philosopher Nancy Fraser calls “Cannibalistic Capitalism,” which also is the title of her latest book in which she describes the state of things thus:

“[…] capitalists appropriate the savings in the form of profit, while passing the environmen[1]tal costs to those who must live with – and die from – the fallout, including future generations of human beings. More than a relation to labor, then, capital is also a relation to nature – a cannibalistic, extractive relation, which consumes ever more biophysical wealth in order to pile up ever more “value,” while disavowing ecological “externalities.” […] Like the ouroboros, it eats its own tail.”

While governments can intervene to lessen the damages already done, it seems they are always a step behind, “ because they leave intact the structural conditions that license private firms to organize production, they do not alter the fundamental fact: the system gives capitalists motive, means, and opportunity to savage the planet.”

QUICK FIXES, COMBINED LONG FIXES, OR TOO LATE?

The path towards a sustainable future necessitates reimagining norms. Attempts at reinventing and reshaping what is bad for the climate involve alternatives to our consumption, such as plant-based meat or purchasing carbon offsets when flying. A crucial question this implies is whether it is indeed possible to consume our way towards a sustainable society? Is it even possible to find a sustainable balance between economic stability, social well-being, and environmental protection? Our global culture has gone from a market economy to a market society. And while economy is a valuable and highly effective tool for organizing productive activity, a large part of humanity lives a life in which market values seep into every aspect of human endeavor. This evokes the by well-known quote, often ascribed to Slavoj Žižek or Frederic Jameson, that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” The human condition of relentless craving for both more and better, deeply embedded in the consumerism of our time, has reached a critical peak. Like Erysichton in the myth of Demeter’s curse, it seems we are about to consume the very conditions necessary for life on Earth to survive if we continue our current path. The prevailing economic system today mirrors Demeter’s curse of insatiable appetite. This system of consumerism and commodification relies on coerced labor, land expropriation, and racialized zones used as dumping grounds for used clothes, shoes, or toxic waste. The widely read Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing The Mushroom at the End of the World – On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, 2015 offer a slightly different view on the current capitalist and climate order. She takes her point of departure in the Matsutake mushroom which thrives in disrupted landscapes caused by capitalist activities like deforestation or nuclear disasters, and combines it with the idea that the human capitalist deconstruction of the world as is, will be working collectively with all other life and organisms to create something else, something that can give a shimmer of hope in a post-climate catastrophe world. “Making worlds is not limited to humans. We know that beavers reshape streams as they make dams, canals, and lodges; in fact, all organisms make ecological living places, altering earth, air and water. Without the ability to make workable living arrangements, species would die out. In the process each organism changes everyone’s world. Bacteria made our oxygen atmosphere, and plants help maintain it. Plants live on land because fungi made soil by digesting rocks. As these examples suggest, world-making projects can overlap, allowing room for more than one species.”

Through this lens resilience of nature and the complex webs of relationships in ecology can emerge during global economic and environmental transformations even after man as species has been extinct. The concept of NIMBY (Not in My Backyard) highlights how certain communities, particularly marginalized or racialized ones, unfairly bear the burden of waste disposal and environmental hazards. As the effects of colonialism are still active – with settlers appropriating and expropriating land, often while violently displacing Indigenous peoples and imposing their own culture – it raises legitimate questions about global resilience and the possibility of finding solutions that prioritize justice, equality, and peaceful coexistence sooner rather than later. Changes in a global order from any perspective, bureaucratical or from a grass roots perspective, normally go through the stages of becoming aware of problems, then taking the step of gaining knowledge. After these stages are fulfilled, action can be taken.

The artists that participates in The Curse of an Unstoppable Appetite are presented in a thematic order of awareness, knowledge, and action with experimentation/investigation, hereby emphasizing the exhibition‘s unified identity across multiple venues.

CHAPTER 1: ODORS FROM THE UNDERBELLY

Spriten Kunsthall

Over the last 100 years or so the Roma people were collecting scrap metal, recycling it. It’s only recently that [modern Western] societies began thinking of recycling as something important.

Selma Selman engages in a multifaceted practice that combines activism, feminism, and art. Through her work, Selman confronts and subverts societal power dynamics, particularly addressing themes of discrimination, violence, patriarchy, and sexism experienced within her community and beyond. Her art reflects her firsthand experiences and collective identity as a Romani woman. Selman’s performances are marked by actions, such as dismantling electronic waste with her family in the ongoing project Motherboards, challenging narratives around sustainability and power. She repurposes and transforms objects symbolizing status into statements of resilience and resourcefulness, and hereby explores themes of transformation and value creation, much like a contemporary alchemist.

By deliberately positioning herself as an artist of Romani origin, Selman reshapes narratives of identity and representation, advocating for the empowerment and visibility of oppressed women. Selman’s artistic practice is marked by a visceral expression of rage, serving as a potent critique of societal injustices. Through performances wielding axes and power tools, or charging at mechanical equipment such as Mercedes cars, she confronts and challenges prevailing narratives of discrimination and oppression. Her confrontational approach reflects a deep-seated urgency to reverse power dynamics and dismantle systemic barriers faced by marginalized communities.

The motivations behind European migration to the Americas after 1492 were often summarized as the ‘three Gs’: Gold, God, and Glory. Additionally, the reality of genocide, a fourth ‘G’, later facilitated what became known as the American ‘gold rush’ in subsequent years. When reflecting on the ancient social contract that led to gold becoming the standard currency instead of any other element, the choice might seem somewhat arbitrary. Pyrite, a mineral commonly known as ‘Fool’s Gold’ due to its deceptively similar appearance to real gold, is a concept that Löfström explores in her installation. The installation brings together elements of fool’s gold, ring-lights often used to smooth facial shadows in the social media echo chambers, and plants used for medicinal purposes to induce visions (some hallucinogenic) and heal mental states.

Through her installation, Löfström explores these historical and symbolic connections, juxtaposing materials, and concepts to provoke contemplation about the complex interplay of wealth, faith, ambition, and darker human realities. Löfström’s second work in the exhibition – the looped video piece titled Vanitas, 2021, features an animated abstracted dendrogram – or mandala, a symbol representing the cosmos – that portrays the cyclical rise and fall of all species on Earth. The title alludes to the genre of still-life paintings that symbolize life’s transience and the inevitability of death. This connection highlights how human influence has accelerated ecological decay. Vanitas serves as a visual poem reflecting on the fleeting nature of existence and the profound impact of human actions on the intricate tapestry of life on Earth.

Kunsthall Grenland

Decolonialism is a theme that often appears in the work of Sammy Baloji, raised in Lubumbashi (Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly the Belgian Congo and Zaire), a center of colonial problems related to resources. He addresses the dematerialization of the landscape and the delocalization of precolonial social systems through colonial action. Baloji’s film Aequare. The Future that Never Was (2023), shown as part of a larger installation in the Belgian pavilion in the Architecture biennial in Venice 2023, mixes colonial-era promotional reels about farming and mining in his native Congo with contemporary footage of similar practices. The film shines a light on the ecological destruction colonialism has caused to the world’s second largest rainforest (around Yangambi). We get to go back in time and see the vision of a future from the colonialists’ perspective in and around the Yangambi Agricultural Center, in combination with newly shot footage of obsolete colonial buildings occupied by Congolese agents and workers.

In several works, Baloji has shed light on and re-reads the impact and traces left by the colonial mining in the province of Katanga, rich in raw materials in the Democratic Republic of Congo, be it cultural, industrial, or architectural. The gap between yesterday and today is not so wide, considering today’s economic imperialism that reinforces the power relations of yesterday.

Spriten Kunsthall and Kunsthall Grenland

Artist Simon Mullan explores charged socioeconomic associations tied to objects and relations in his practice. The phrase “I am a lawyer seamstress/printer/musician” signifies not only aspects of everyday life and conditions for individuals but also conveys a sense of personal identity and pride in one’s craftsmanship. To tie one’s identity to the workplace is particularly relevant in much of the Western world. These discreet aspects manifest in various elements of our identity, including our attire, speech, transportation choices, and dietary preferences, all of which signal our affiliations and associations.

Mullan has engaged with some of the workers at Porsgrunds porcelain factory and Ulefos, one of Norway’s oldest functioning heavy factories, established over 350 years ago. The industry’s legacy and the relationships between owners and workers permeate the surrounding landscape and architecture. The patrons’ mansion stands adjacent to the factory, while some workers’ cottages have been transformed into an open-air museum, preserving the historical lifestyle under enthusiast care. Such heavy industrial complexes are becoming increasingly rare in Europe due to outsourcing to countries with lower labor costs and regulations. Mullan is intrigued by the interaction between work and leisure. How do workers dress during their shifts, and how do they present themselves on their days off? His primary focus within the factory environment is on the individuals employed there. He presents a series of portraits alongside steel grids manufactured at the factory. In a conversation, Mullan likened the function of these grids, typically used for cleaning shoes in public spaces, to that of an artist. He believes that, like the grid, an artist operates within society to rinse it from impurities and dirt to capture human behavior. It is easy to draw parallels to the portraits of August Sander, who sought to capture his contemporary reality as it was, thereby reflecting the strata of his era. Similarly, Mullan’s portraits serve this function, yet they also reflect a class reality that is on the verge of change.

Simon Mullan talks about his work Arbeitswelten exhibited at Spriten Kunsthall in the exhibition The Curse of an Unstoppable Appetite for Greenlight Triennial. In Swedish. Camera and production: Juan-Pedro Fabra Guemberena.

CHAPTER 2: “TO ANY CELESTIAL BODY, LIFE IS NOTHING BUT AN ILLNESS”

Kunsthall Grenland

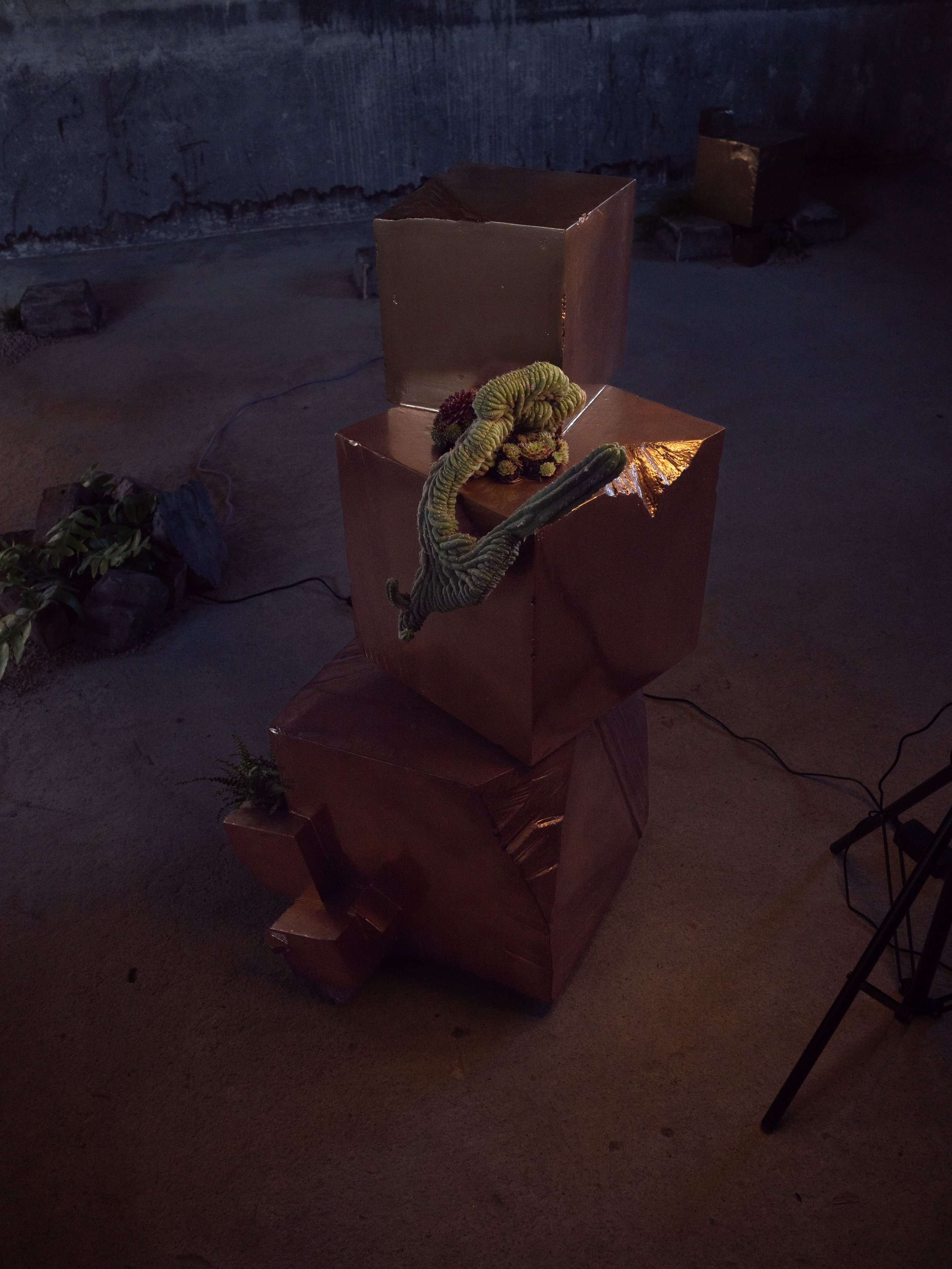

Installation image from Kunsthall Grenland

Lara Almarcegui has been working on an ongoing series of projects titled Mineral Rights since 2015. Almarcegui actively pursues mineral rights across multiple countries, documenting her endeavors and setbacks which entices discussions on land ownership and mineral rights regulation. How to get the rights vary widely from one country to another, and it is customarily impossible for a private individual to acquire them. Her work challenges how territories are shaped geologically and subsequently exploited for economic and political gain through corporate extraction. Almarcegui acquired exploration rights to an iron deposit in Tveitvangen, Norway, some time ago, and is presented in Norway for the first time in the exhibition. With the keen assistance from Greenlight Triennial and Kragerø Kunstskole, Almarcegui has managed to renew her rights that had expired, with the aim of keeping this plot unexploited for as long as possible.

Through her work, Almarcegui questions societal norms and relationships with the Earth, critically examining how these intersect with scientific and legal frameworks. Central to her inquiry is the ownership of extraction rights and the subsequent monetization of common resources – who benefits and who loses out? As the exploitation of resources often leads to environmental degradation, affecting future generations with contaminated water and depleted land, Almarcegui’s work advocates for safeguarding the rights of future generations against such consequences.

Skiens Kunstforening

The artwork titled Lonesome George by Ayşe Erkmen is a small bronze sculpture displayed in a public park outside the Ibsen House/Skien Kunstforening. This 1:1 replica represents a Hawaiian tree snail (Achatinella apexfulva), specifically so, the famous specimen known as Lonesome George, which resided in a laboratory on Mānoa for more than fourteen years. Scientists fruitlessly sought a mate for “the world’s loneliest snail” during these years, and with Lonesome George’s death in January 2019, the species became extinct – a poignant example of global species loss. This is not a situation unique for Hawaii, it is something that happens around the planet. Today, one million animal and plant species are at risk of extinction, with many amphibians, birds, and mammals already gone forever. Habitats are disappearing, imperiling essential pollinators like bees and butterflies crucial to our ecosystem. Conservation organizations and researchers have undertaken efforts to preserve and breed species through captive breeding programs. Some individuals are housed in managed facilities to prevent complete extinction, and potentially reintroduce them to their natural habitats in the future. The bronze cone-shaped snail shell serves as a tribute and monument to a vanished species. It stands as a serene reminder of humanity’s neglect – not only towards other species on Earth but also towards the ecosystem that faces perpetual disruption due to our relentless consumption. Conversely, there is a fatalistic, deterministic viewpoint regarding the fate of our world, suggesting that life is akin to an illness – an infection or microorganism – on any celestial body. This perspective implies that the destructive path we are currently on is a consequence we have earned.

Skiens Kunstforening

The artist duo Mats Bigert & Lars Bergström, renowned for their pioneering exploration of climate breakdown and environmental sustainability over decades, seamlessly weave together humanity, nature, and technology with wit and critical insight. Their large-scale installations dissect complex social and scientific issues in visually captivating ways. The installation Geode (Wrecked Wrecking Ball) builds upon and repurposes past artworks, featuring a monumental broken black sphere filled with dried clay fragments. This wrecked ball indicates the deteriorated state of urgent global issues, resembling a demolition wrecking ball. Adjacent to the Geode (Wrecked Wrecking Ball), are five ice-shard sculptures titled Crystal Forests. The work is inspired by J.G. Ballard‘s The Crystal World, which portrays a world where nature crystallizes and turn into precious stones due to a decease. Those who try to harvest the newfound riches get caught within crystallized shells.

CHAPTER 3: POSTERITY. OR BEYOND

Telemark Kunstsenter

The current global structure presents limited opportunities for future generations. Philosopher John Rawls proposed in his book Theory of Justice, that progress towards a more just and equitable world requires entrusting leadership to individuals who approach decision-making with a “veil of ignorance,” unaware of their own identity markers such as gender, skin tone, class, or health conditions. Only in this state of impartiality can they strive to create a world with improved justice.

Since 2016, artist Stine Marie Jacobsen has been developing an art project called Law Shifters, focusing on global law by involving people in reevaluating court cases and drafting their own laws. In the Law Shifters project, which has operated in several countries including Lebanon, Chile, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Greenland, Ukraine, and the UK, Jacobsen recently embarked on an abstracted court case for the first time. The objective is to inspire unconventional discussions that transcend fatalistic and conven[1]tional reasoning, sparking radical imagination. To achieve this goal, Jacobsen conducted a workshop at Telemark Kunstsenter with four participants from the area, aiming to stimulate non-normative and speculative discussions and role-playing scenarios related to climate laws and displacement. Jacobsen encouraged participants to think beyond typical human perspectives by challenging them to describe a purposeless judicial system and to reason as either an animal, a technological device, or the soil. Amidst escalating challenges of climate migration and mobility resulting from climate change-induced disasters like rising sea levels, coastal flooding, and severe drought, concerns about mass climate migration are growing globally. Paradoxically, the term “climate migrant” lacks legal recognition, with governments failing to offer legal protections for affected individuals. Climate-related disasters cause more internal displacement than conflicts, yet the concept of climate migration remains predominantly within the realm of policy-oriented research. Is it possible to safeguard future generations by creating bold, forward-thinking climate legislation? In one unique campaign to save the Mar Menor ecosystem, Europe’s largest saltwater lagoon, resulted in the passage of a new law in 2022, granting the lagoon legal rights after becoming polluted due to mining and other environmental challenges as a result of urban infrastructure. Jacobsen’s approach is experimental, and the outcome is an animated film with five characters (the fox, the soil, the mobile phone, the drill and the slime ball narrator) which discuss what ought to be allowed to do or not.

Spriten Kunsthall

Siblings Maëva and Arnaud Grapain collaborate as Collectif Grapain, creating diverse artworks across various mediums that incorporate scientific experiments, science fiction, and futuristic aesthetics. They explore topics such as nuclear waste and the emergence of life on it in spite of its toxicity. Drawing inspiration from post-apocalyptic scenes, Collectif Grapain engages with ‘neo-archeology,’ which examines past cultural systems through their remnants and speculates on how future archaeologists might interpret our present culture. In a world devastated by climate change, where soil is too contaminated for planting and sunlight struggles to penetrate toxic air, what will endure? Our legacy will likely comprise discarded technology, expired materials, industrial remnants, and hazardous waste. Modern zombies and computer data serve as evocative allegories in their work. Using unconventional materials such as Ethernet cables and rock wool, the collective sculpts alternative landscapes. Ethernet cables are transformed into textured sculptures resembling archaeological remnants of unknown species, symbolizing a world hostile to biodiversity. Rock wool covers enigmatic structures, evoking centuries-old wrecks emerging from water.

Collectif Grapain presents a film Sans Soleil (Without Sun), 2024 in combination with sculptures constructed by melted internal components from technological devices in a “pyro-process”, hereby creating artificial lava. They aim to fuse cultural remnants into hybrid amalgamations, returning rare earth elements (REE) to their geological origins. The nine-minute film depicts a staged post-apocalyptic landscape where wild fires have ravaged the land. The sun becomes a metaphor of a nuclear reactor that destroys everything in its path. It is a symbol of the dual nature of nuclear power, a source of energy and also the tremendous capacity for destruction and catastrophic consequences.

TANYA BUSSE & EMILIJA ŠKARNULYTĖ

Kunsthall Grenland

New Mineral Collective describes itself as “the largest and least productive mining company in the world”, operated by artists Emilia Škarnulytė and Tanya Busse. They aim to challenge the extractive industry using alternative approaches such as desire, body mining, and acts of counter prospecting. The concept of counter prospecting seeks to reframe and also resist the impacts of expropriation, exploitation and nature extraction. Can we extract meaning instead of just material? Rather than simply depleting the earth’s resources, how can we foster imagination and explore new possibilities? New Mineral Company will exhibit the film Pleasure Prospects, commissioned for the 1st Toronto Biennial. The film comments on the patriarchal structure of extracting and prospecting the earth, and the need for a counter perspective to extractivism. “Penetration is our destination” recites the arctic drilling corporation. How to read the earth surface, not as a skin, forever penetrable, vulnerable, viable, gendered but as a surface? How to pierce the violence and not the surface? Pleasure Prospects reimagines the process of acquiring prospecting licenses, challenging the traditional extractive mindset. It promotes a reparative approach focused on desire, love, poetry, and resistance rather than relentless productivity. The New Mineral Company advocates for “unproductivity” to halt environmental destruction, acknowledging the existing damage and seeking to transform harmful narratives.

TANYA BUSSE

Spriten Kunsthall

Tanya Busse’s work Wind Sings to Wire consists of dozens of lightbulbs connected to the architectural space of Spriten Kunsthall via industrial cables, with the flickering lights suggesting interference from another time and place. This flickering is suggesting a signal transmitting data from the year 2030, a critical milestone often cited for the year when the irreversible climate change happens and the tipping point for the global sustainability goals, including the Paris Agreement and Renewable Energy initiatives. Early last year, the Norwegian government approved a plan to connect the Hammerfest liquified natural gas plant to the power grid, with the installation’s beat and pulse based on electricity forecasts, energy predictions, and futurological mappings of that plan.

The year 2030 also marks a significant transformation for Melkøya, an island in the Barents Sea, where the large pro[1]cessing facility for liquefied fossil gas from the Snøhvit oil and gas field will be fully electrified. The planned infrastructure expansions in northern Norway pose extensive risks to the environment and indigenous lands. These plans carve an entirely new spatial geography while many factors remain unpredictable, including electricity prices, the impact of thawing permafrost on water supply and infrastructure, climate migration, and other unseen forces.

Remarkably, concerns about the climate impact and ongoing violations of Sami rights and the colonization of indigenous territories are currently being completely disregarded. Supporting the transition of Melkøya requires an extensive network of electric grids, power lines, roads, wind turbine parks, and hydro dams. Busse’s installation reflects the flickering and weak prospects of future possibilities, inviting the audience to immerse themselves in the site-specific installation to experience light as information – a message from the future symbolizing ambiguity and uncertainty. We rely on advanced technology every day, aware that these structures may fail us, just as human factors can fail. This implies a loss of control and a fragility in our established order. In the Telemark region, there are currently 17 dams and an enormous demand for megawatts, especially with a new hyperscale data center on the horizon. When we make plans for the future, stability and hope for a better life are always the goals.

How can we ensure prosperity and comfort when so many factors of instability and scientifically proven concerns are ignored? If we could send a message to the miners of Søve Gruve in the 1930s or 1940s from our current times, what would it be?

Telemark Kunstsenter

Chiara Bugatti considers materials as vital carriers of memory, identity, and value. Reflecting on marble, a material she frequently uses, she remarked: “Consumerism has developed a tendency to separate ourselves from the natural world. Giving language – a soundless, timeless voice – to the calcium carbonate in marble and the polychlorinated biphenyl in the soil is an attempt to flatten the hierarchical system where human development is always prioritized.” After visiting Telemark, Bugatti traced the local history and geology, exploring their impact on everyday life through materials. By studying the formation, transformation, extraction, and use of stone, she uncovers themes of vulnerability, ambition, hierarchies, and failure. The concept of the volcano in Fen, which spewed liquid limestone to create precious metals and transformed the Earth into a hollow body with giant capillaries that sustain human life, deeply influences her work. This idea of ambiguous and imbalanced scales and proportions is embodied in her installation, Giants. Bugatti’s artistic process raises questions about possession and power, and whether humanity can find ways to coexist responsibly with the resources and material bodies we depend on.

Chiara Bugatti on her work Giants installed at Telemark Kunstsenter in the exhibition The Curse of an Unstoppble Appetite for Greenlight Triennial. In Swedish. Camera and production: Juan-Pedro Fabra Guemberena.

Spriten Kunsthall

Rina Eide Løvaasen presents a multi-layered and visually joyful storytelling in her ongoing project titled A Story Is True Only When It Is Complete, which she describes as a Gesamtkunstwerk. Parts of this expansive work will be showcased in the exhibition. Her installation at Spriten Kunsthall includes diverse elements such as textile paintings and sculptures crafted from stones harvested from the region, notably the Fensfelt. The textile work features digital jacquard weave embellished with silk thread, pearls and paillettes. Each layer of the triptych holds symbolic significance. The weave’s composition forms a fictive nebula, mapping out resembling the Spomeniks of former Yugoslavia – monumental concrete structures commemorating events from World War II from a country that does not exist anymore, here portrayed as burned-out stars in the sky. The work incorporates two distinct sources: an extinct bird, a tiny jellyfish, and a pokémon. The Hawaiian bird, Kauaʻi ʻōʻō or ʻōʻōʻāʻā (Moho brac[1]catus), represents a lost species due to ecosystem disruption by introduced predators. The Turritopsis nutricula jellyfish, known for its unique ability to reverse aging – an intriguing subject for scientists exploring longevity. Accompanied by egg-shaped sculptures crafted from local stones – Søvitt (containing niobium), Rauhaugitt (containing rare earth elements), and Rødstein (containing thorium) – Løvaasen’s work weaves together potential narratives of tomorrow’s and future mining at the Fensfelt. It considers an ecosystem contaminated by radioactive waste from yesterday’s mine, forming a captivating mythology of its own.

Spriten Kunsthall

Damien Ajavon roots their artistic practice in their heritage, exploring diverse methods of manipulating textile fibers by hand, including knitting, knotting, braiding, tangling, and weaving. The interaction between visual and tactile experiences is central to their process, drawing on both African and Western influences to convey unique creative approaches and tell textile stories. Ajavon utilizes textile languages, rather than oral ones, to forge connections with their ancestry, honoring African cultures through artistic gestures while embracing local materials during their residency in Skien in 2024–25. Thus practicing sustainably and paying tribute to the Norwegian ancestral use of local resources, for instance nettles. Ajavon’s fascination with the region’s rich bio[1]diversity drives them to investigate native plants for sustainable materials and methods to work with. They will conduct a thorough exploration of the unique flora, harvesting plants to create yarns and natural dyes extracted from leaves, flowers, and roots. This process will be showcased in the exhibition, allowing the audience to witness firsthand the creation of sustainable textiles. In addition to textile arts, Ajavon will explore culinary uses for the harvested plants, from nourishing soups to herbal teas. By fostering this connection with nature, they aim to promote a more sustainable future and inspire others to appreciate and protect the local biodiversity.